Alaska birch aphids: a taxonomic story

We were sitting in our sunny garden a few days ago, and saw a

glistening rain falling from the birch trees, which were just leafing

out. But it wasn’t liquid drops... it was a shower of insects. We then

noticed the many tiny, green aphids that were crawling all over us. A

plague of aphids? Yet more climate-related trouble for 2016? Now, the

advantage of being interested in natural history in the US, as opposed

to Indonesia, is the great amount of information available, and

googling ‘aphid birch alaska’ I found numerous references to the

Alaskan ‘birch aphid,’ generally named as Euceraphis betulae (Koch.)

(e.g.,

this USDA report). These

insects overwinter as eggs, hatch in the spring, and immediately

reproduce parthenogenetically (without mating), thus increasing their

population very rapidly. Usually they cause little damage to their

hosts, due to their many predators (the ladybird bugs are out too!).

But I was puzzled by their taxonomy. Most of the literature on Euceraphis betulae relates to its occurrence in the U.K., where it feeds on silver birch (Betula pendula). I checked further, but it does appear that Euceraphis betulae is the name generally (historically) used in Alaska (e.g., the Checklist of the Hemiptera of Canada and Alaska, GBIF, SpeciesFile, ARCTOS, etc). Was this species introduced from Europe? Is it naturally circumboreal? Several references pointed out the high host specificity of Euceraphis species: in the the UK, Euceraphis betulae feeds on Betula pendula, and Euceraphis punctipennis on Betula pubescens (see this great site). This European specificity makes it less likely that Euceraphis betulae is here in Alaska. I then saw Euceraphis betulae described as covering a “complex of non-European species,” and also found reference to Euceraphis borealis in Alaska (hmm... that sounds better!). So I looked into the taxonomy of Euceraphis more carefully.

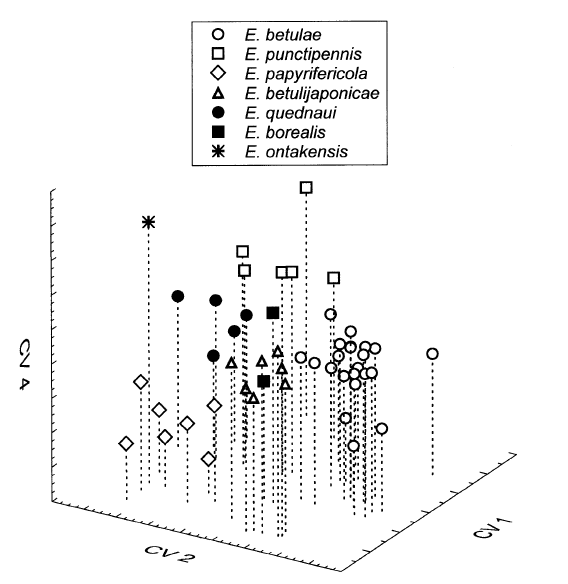

Figure 1. Variation in orthogonal morphometric space of individuals assigned to different species of Euceraphis.

The authority on Euceraphis is Roger Blackman, of the UK Natural History Museum. In 1977 he described the two UK species, and in 2002 published a cool study (with Emma De Boise) of the morphometrics of Euceraphis from all over the world. They found that the individuals from different host plants spread out quite clearly in ‘multi-dimensional morpho-space’ (based on thirteen physical measurements of the insects; Fig. 1), and thus could potentially be diagnosed as different types. On this basis, they described three new species: Euceraphis borealis Blackman (on Betula glandulosa and Betula nana), Euceraphis papyrifericola Blackman (on Betula papyrifera, and Euceraphis quednaui Blackman (on Betula occidentalis). So... what we have here in Alaskan paper birch forest seems actually to be Euceraphis papyrifericola (I also noticed belatedly that BoLD, the Barcode of Life database, has 1,413 samples correctly labeled as Euceraphis papyrifericola). The ‘dwarf arctic birch’ (Betula nana) of the North Slope and mountain alpine zones should have Euceraphis borealis on it. Should you stumble across an aphid on a birch in Alaska and be interested in IDing it, no problem! Here is the relevant couplet of the key (to the winged stage):

- Base of antennal segment VI 2.35-3.10x longer than last segment of rostrum, which is 0.11-0.14 mm long, 0.52-0.62x length of hind tarsus segment II = borealis;

- Base of antennal segment VI 1.24-2.72x longer than last segment of rostrum, which is 0.12-0.19 mm long, 0.55-0.93x length of hind tarsus segment II = papyrifericola

Easy, no! ;-)

But what this underlies for me, and why it is so exciting, is that it is yet another case of the taxonomy of organisms in Alaska being not as cut and dried as I had expected: here is an economically important, very common species being only just named in 2002. Both other cases I’ve looked into so far (willows, and Cornus canadensis) are also messy and interesting. All this is not so very different from the challenging situation we have in Southeast Asian plants. Bottom line: there is so much more to discover, even where we think it’s all well known!